Uncovered: S.C. tax agency didn't enforce oversight rule as Hampton County misspent millions; Sumter, other counties didn't report penny tax spending

This article is part of The Post and Courier's Uncovered project, an ongoing initiative to shed light on corruption in South Carolina. The Post and Courier has partnered with 18 community newspapers, including The Sumter Item, across the state to bring investigative journalism to light. To read more Uncovered articles, visit www.postandcourier.com/uncovered.

tmoore@postandcourier.com

HAMPTON — Long before this county misspent a single dollar of its residents’ sales taxes, it broke a law intended to safeguard that money.

Three months later, it did again. Then again and again and again, every quarter for the better part of a decade.

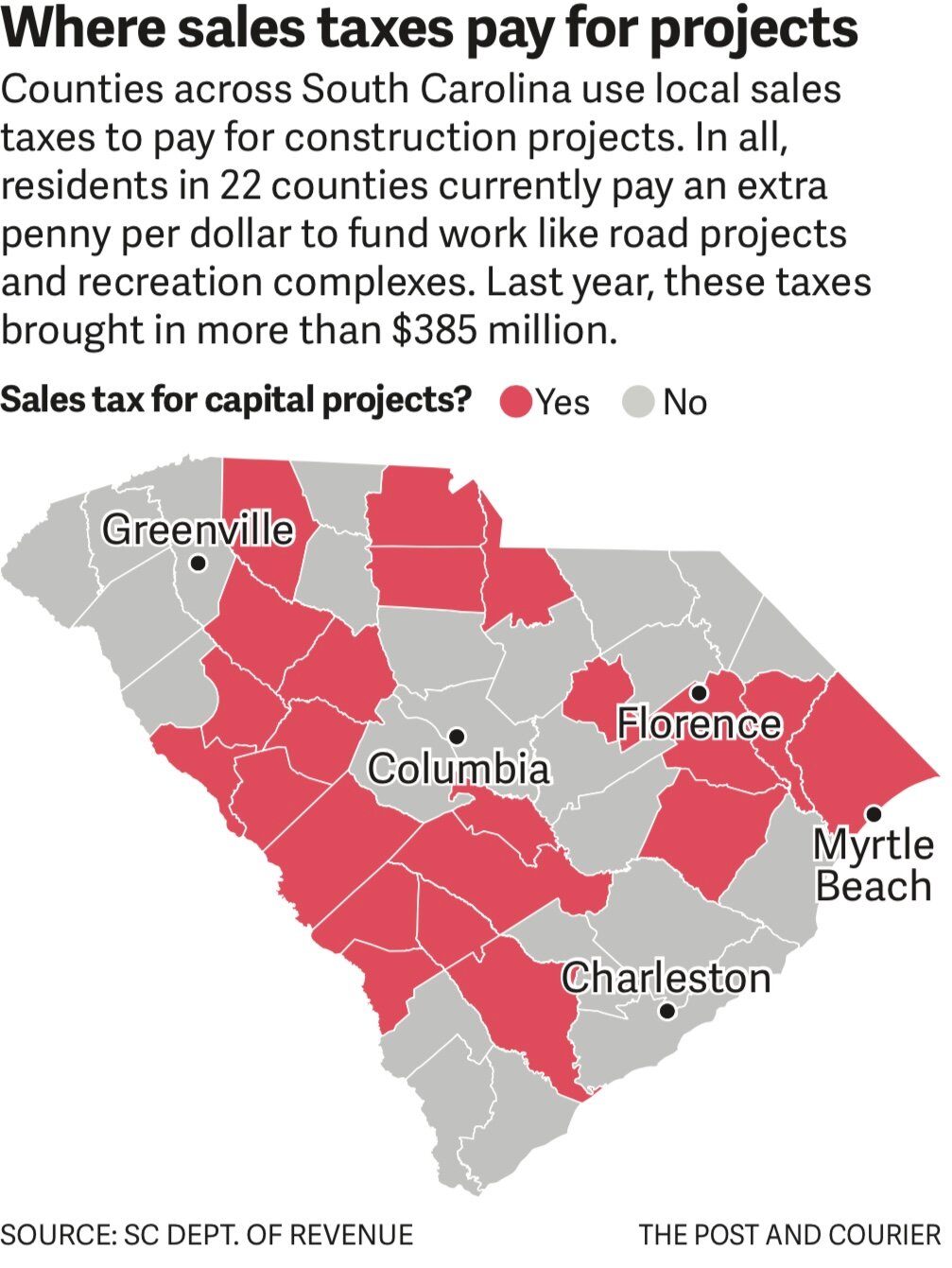

Counties are allowed to impose higher sales taxes to bankroll big projects like building roads and renovating their facilities. But in return, they’re required to send the state quarterly reports about how they’re using that money.

Hampton County didn’t comply with that law once in the eight years it collected the extra tax. It sent the S.C. Department of Revenue just one spending report, a year after its tax ended. By then, county officials had discovered at least $3.1 million was missing from the sales tax fund, setting off a firestorm among the county's residents.

The Department of Revenue, the state’s tax agency, did not take notice of the missing reports, even as the county blew through more than 30 deadlines, according to an investigation by Uncovered, The Post and Courier’s initiative to shine a light on questionable government conduct in partnership with community newspapers around South Carolina.

What’s more, Uncovered found, Hampton County was no exception in violating the law.

Almost half of the state’s counties — 22 of 46 — charge their residents an extra penny per dollar for construction projects. All but one failed to report their spending even once this year, according to records produced by the Department of Revenue in response to an open-records request.

Now, the agency says that will change. After Uncovered asked questions about the oversight, the Department of Revenue sent instructions to counties around the state, asking that they start sending reports next year.

“I’m sure they’re going to,” said state Senate Minority Leader Brad Hutto, who backed the requirement when it was passed in 2002. “Because if they don’t, we’re going to make ‘em.”

Sumter County

In Sumter County, voters approved the Penny for Progress in 2008 and again in 2014 but voted down the measure in November 2022. The most recent penny tax ended April 30 this year.

According to the records produced by the Department of Revenue in response to The Post and Courier’s open-records request, Sumter County was one of the 22 South Carolina counties to not report its penny tax spending to the Department of Revenue this year.

2023 is the final year Sumter County is required to send the state quarterly reports about how it is using that money because the county stopped the penny tax in April of this year after voters didn't renew it a third time.

The Sumter Item asked for comment on this from the county’s treasurer and did not hear back.

New tax, new requirement

Twenty-six years ago, South Carolina lawmakers set off a feeding frenzy among local governments eager to take on big projects without the state’s help.

In an effort to tamp down property taxes, they let counties pay for projects with new sales taxes instead.

But lawmakers did not want to give them too much leash. Before they could raise taxes, each county would have to convene a panel to decide what projects the money would go toward and what order to take them on. Then, voters would have to approve the plans in a referendum.

Soon after the Capital Project Sales Tax Act became law in 1997, counties jumped in. Spartanburg and York saw an opportunity to widen roads. Orangeburg wanted to pave dirt roads and build recreation facilities. Newberry wanted to renovate its courthouse and the county-run emergency room.

The new tax would become an important source of money for local governments. Last year, capital projects taxes brought in $385 million.

As the first round of taxes came up for renewal, lawmakers decided South Carolinians needed more assurance their money was being used the way county leaders said it was. In 2002, they tucked a new requirement into an all-encompassing bill that changed the state’s rules for bingo halls and economic development incentives, among other things.

Under the new law, counties would be required to tell the state every three months how much money they’d spent on each of their projects. The requirement was initially proposed as part of a bill sponsored by former state Sen. Wes Hayes, R-Rock Hill.

His home county, York, was the first county to pass a penny tax in the 1990s, and it has had one ever since, using it to keep up with the growth of Charlotte’s suburbs. But support was tenuous at first, and the initial referendum barely passed. Hayes said lawmakers implemented a reporting requirement to assure voters that the tax would be used to get construction work done, not grow government.

Orangeburg County was also quick to adopt a tax. There, Hutto, D-Orangeburg, pushed the reporting requirement before it came up for renewal. Lawmakers thought someone ought to check counties’ work, he said.

They decided to give that job to the Department of Revenue, which collects sales taxes.

But the tax agency says the law only gave it so much power to make counties disclose their spending. For instance, it said, it cannot withhold funding from counties that don’t file reports. The law doesn’t say what the department is supposed to do with them.

Perhaps, Hutto says now, lawmakers ought to clear up the department’s role. For instance, the Legislature could instruct the agency to review the accuracy of counties’ submissions or force it to notify local lawmakers when a county misses a deadline, he said.

Without a clearly defined process, the requirement all but collapsed in the intervening years. The vast majority of counties subject to the rule this year violated it, records show, and the Department of Revenue said it took no steps to enforce it.

“That’s a problem,” Hutto said. “They may say, ‘Well, the Legislature didn’t say if nobody (sent) any reports that we needed to ring the bell.’ I just think that’s kind of common sense.”

In the dark

The discovery that nearly half of South Carolina’s counties were disregarding the reporting rule began with questions in one of its smallest: Hampton County.

Voters there approved an eight-year tax in 2012 to pay for a laundry list of projects: repairs to the county’s decaying jail, a new building for the health department and a new recreation complex among them.

But as the tax entered its final years, residents realized something didn’t add up. A former high school baseball coach named Randy Vaughn was volunteering for the local youth baseball league when he realized the county had reneged on its promise for new ballfields. He was told the county had simply run out of money.

In 2021, Vaughn and other residents began to press county leaders for information, including a retired banker who discovered the county’s books weren’t balanced. They formed a citizens’ group, Hampton County Citizens for Active Restoration, which has spent more than two years calling for a forensic audit.

In response to the public pressure, county officials began to check the books themselves.

In January 2022, they announced their findings: At least $3.1 million had been siphoned from the sales tax fund, apparently to pay for the government’s everyday expenses. (The Department of Revenue is planning to audit the misspent money, county officials say, but the agency has not yet done so.)

The Post and Courier’s Uncovered initiative asked the Department of Revenue for records showing what the county had been telling the state all along. In response to a Freedom of Information Act request, the agency revealed that Hampton County hadn’t been saying much at all.

Though the county should have sent in a total of 32 reports while the tax was being collected, the department said it had a total of just six pages of records on file.

The county had filed a single report, the agency said. It was submitted in April 2022, only after the missing money was revealed. Hampton County treasurer Jennifer Youmans sent it in; she declined to comment, saying she had been “advised not to speak on this matter.”

Officials in multiple counties said they had never gotten a call from the state about the rule, even as they violated it. In fact, they said, they didn’t even know it existed.

Williamsburg County supervisor Kelvin Washington, for instance, said his staff was pulling together reports now that they were aware of the requirement, but he said they had never heard of it before.

“I’m in the dark,” said Colleton County Treasurer Becky Hill. “They’ve never mentioned this.”

And it’s not as though she hadn’t heard from the Department of Revenue, Hill said: The agency audited the county’s capital projects tax just this year.

The only county to file reports this year, Horry, started doing so when it implemented its first tax in 2007 because county staff read the rules themselves, spokeswoman Mikayla Moskov said. It has been a useful exercise, she said, providing "another opportunity for oversight and review."

The Department of Revenue has indicated that it expects other counties to start taking part soon.

In a statement, the agency said it was developing a process for counties to send in information, a first. In an email to counties Nov. 16, it said the first reports will be due a month after the next round of sales tax money is distributed in January.

What will happen if counties still don’t comply, the agency did not say.

Nichole Livengood of The Kingstree News, Elizabeth Hustad of The Post and Courier North Augusta, Jane Alford of The Lancaster News, Michael DeWitt Jr. of The Hampton County Guardian, Damian Dominguez of the (Greenwood) Index-Journal and Bryn Eddy of The Sumter Item contributed to this report.

More Articles to Read