Uncovered: How SC police departments use vague exemptions to block reports from the public

cashworth@postandcourier.com

arockett@postandcourier.com

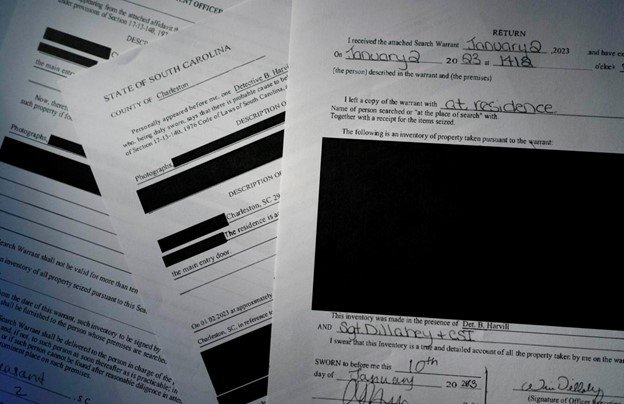

Charleston police went heavy on the black ink when they finally let the public see a search warrant for the home of a prominent attorney found dead there in January. They hid the majority of information, citing a provision in the state’s open records law that allows them to withhold details that constitute an “unreasonable invasion of personal privacy.”

But when reporters with The Post and Courier obtained the very same document from court officials, not a single word was omitted. It showed that among the details police didn’t want you to see were the color of the home’s siding and shutters.

The episode illustrates the widely varying interpretations and misconceptions government officials can have of South Carolina’s Freedom of Information Act, or FOIA. Its loosely-worded exemptions leave the door open for officials to keep public records private and out of the hands of citizens whose tax dollars paid for them.

As the Palmetto State celebrates its open record law with Sunshine Week, information advocates warn that public officials are increasingly using the privacy provision and other exemptions to make the FOIA a mechanism for obstruction rather than a tool of transparency and accountability. And law enforcement agencies are often in the thick of this debate.

The S.C. Press Association runs a Freedom of Information hotline for journalists across the state, and it logs several calls each week from people battling to obtain records from police agencies, according to attorney Taylor Smith, who helps guide reporters who have problems obtaining records. He has seen a troubling trend of public reports being withheld, along with heavy-handed redactions to documents and exemptions being cited unnecessarily.

Such records were made public by the Legislature to help people make informed decisions about safety in their communities and how law enforcement uses their tax money. The information also is crucial to newsgathering, the public’s understanding of government and the democratic process.

“Why not err on the side of transparency?” Smith asked.

Yet examples abound of law enforcement agencies censoring their reports while giving out select details in public statements, a tactic that allows police leaders to control the narrative while leaving few avenues for the public to verify their claims.

In Greenville County, for instance, sheriff’s officials have withheld reports from high-profile incidents until they could prepare “community briefing videos” that contain highly-edited compilations of deputies’ body camera footage, framed with a narration of events from department leaders. The sheriff’s office gives itself 45 days to prepare those videos, as was the case with a January traffic stop in which a teen was wounded by a gun he had in his waistband. The gun fired when deputies tackled him to the ground.

And in Columbia, the city’s police department leans on news releases and public statements from the chief while reports from high-interest incidents are heavily redacted before they are released to the public, often with entire pages completely blacked out.

Columbia Police abides by the state FOIA, said department spokeswoman Jennifer Timmons. She cited exemptions that allow its leaders to withhold records that would interfere with an investigation.

“It is within the Chief’s discretion to release whatever information he deems pertinent, relevant, or necessary for the general public,” Timmons wrote in an email to The Post and Courier.

But blacking out key information, even when details of the crime have already been released by police officials through other channels, suggests the department is employing a heavier hand than necessary, said Carmen Maye, a senior instructor in the University of South Carolina’s School of Journalism and Mass Communications.

“That suggests that these are not good-faith redactions,” she said. “They’re overusing their discretion.”

That department, however, is far from alone in drawing such complaints.

Policing the police

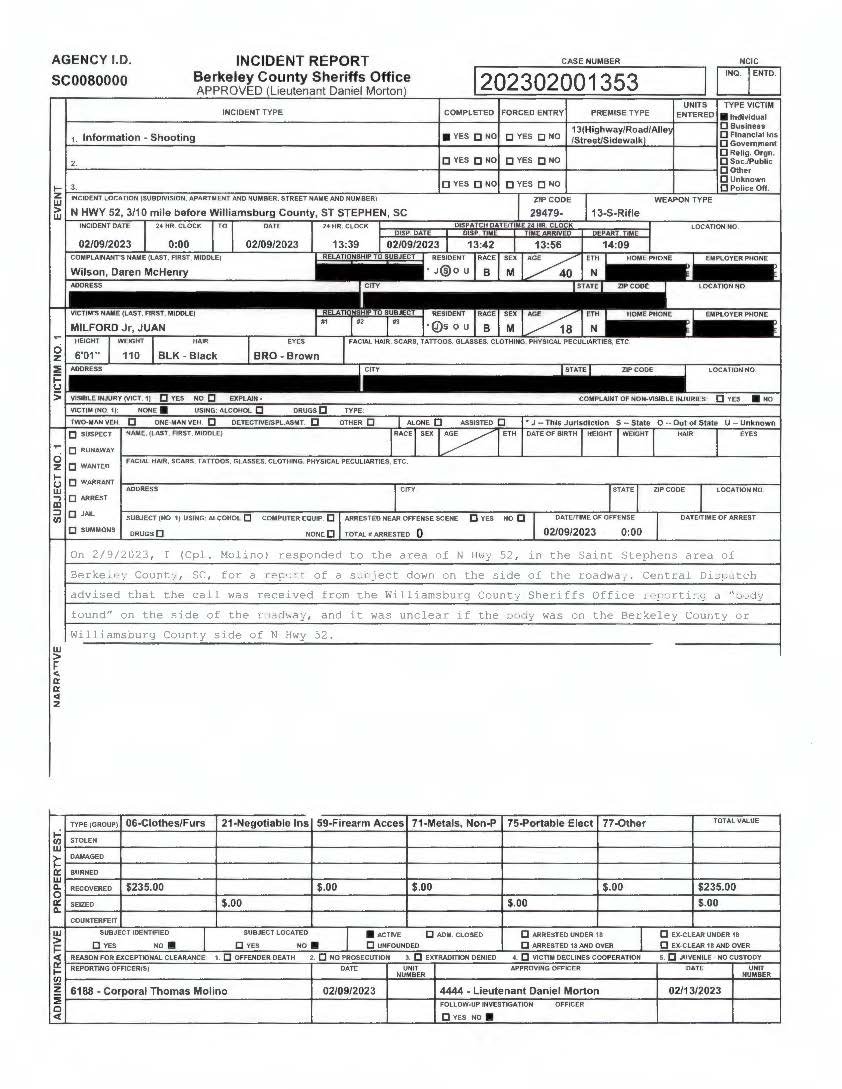

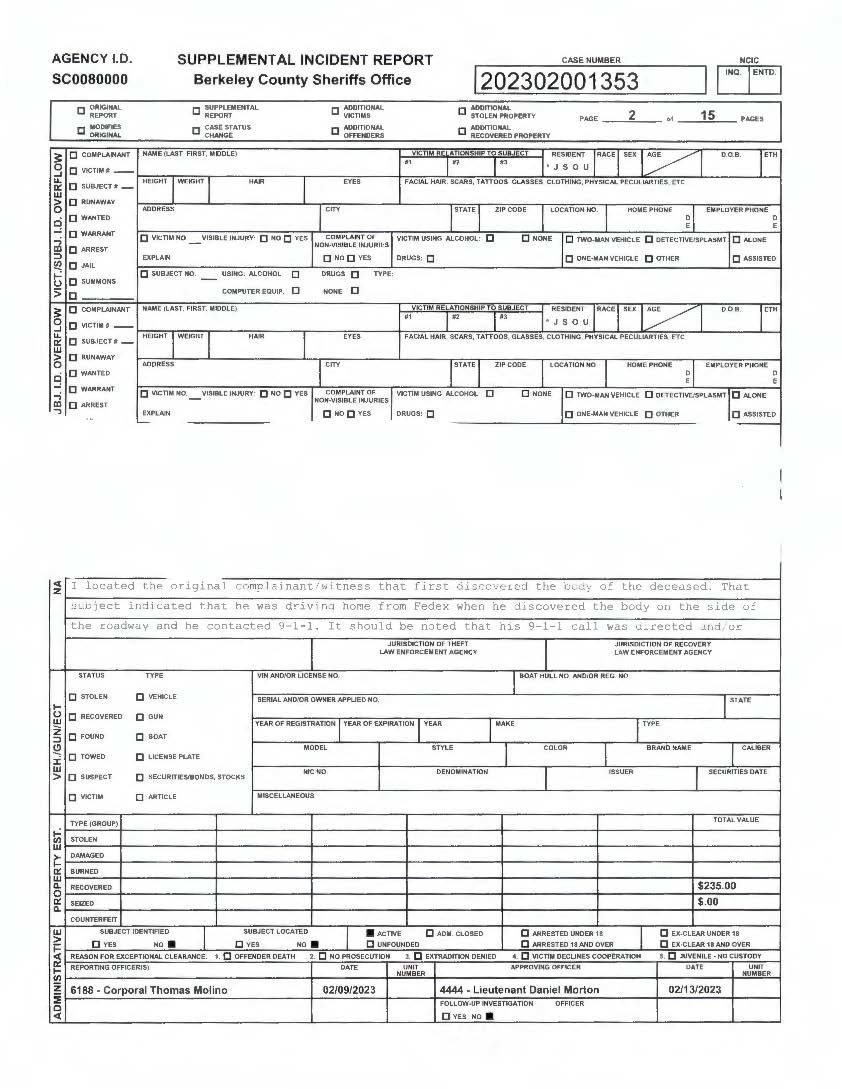

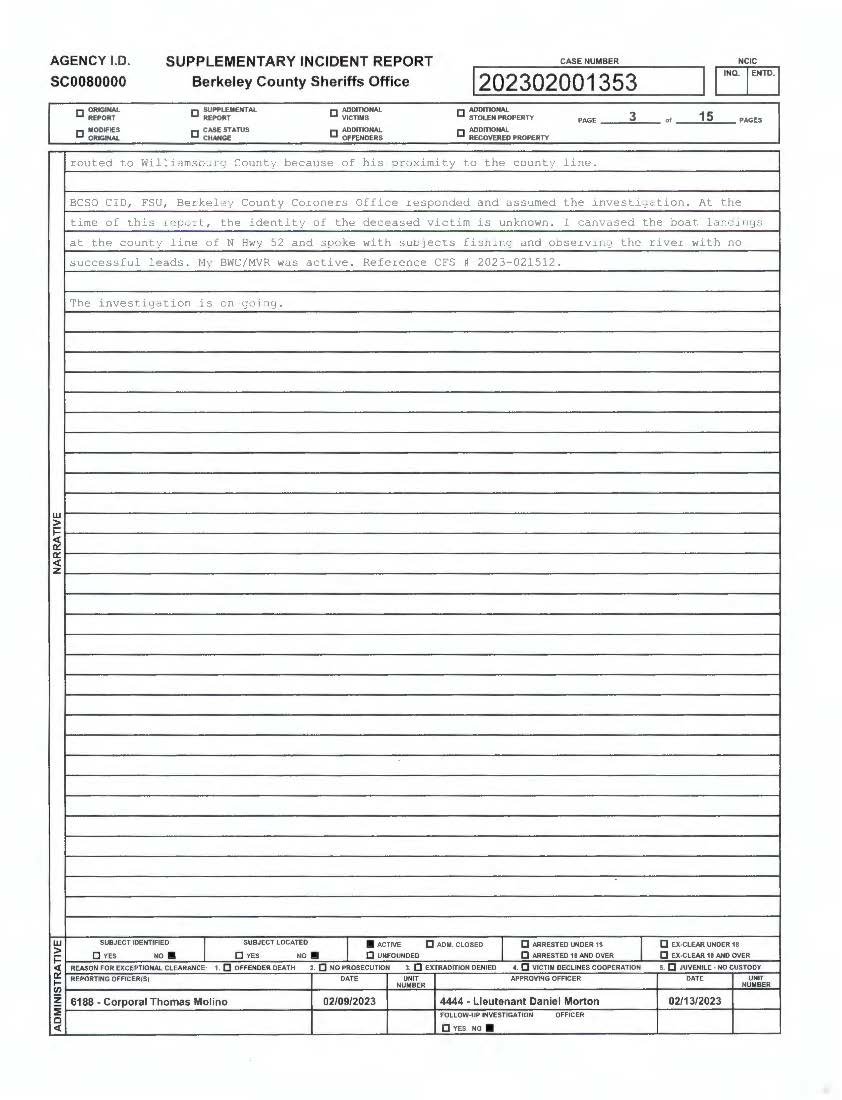

After a body was found along a rural highway in Berkeley County last month near the Williamsburg County line, the Berkeley County Sheriff’s Office issued a short announcement the following day.

Few details were immediately available. More than a week passed before the public was told the deceased was 18, or that he had been shot to death.

Four days after the grisly discovery, the county coroner identified the man and said his death was being investigated as a homicide. The cause of death was not disclosed, with the coroner saying police had yet to make an arrest. This prompted The Post and Courier to ask for the incident report. That document, under state law, is supposed to be available upon request as it discloses the nature, substance and location of a crime.

After repeated requests, and more than a week after the body was discovered, police finally sent the incident report and announced an arrest.

When asked about the delay, Berkeley Deputy Chief Jeremy Baker said the incident report was provided as soon as possible. He said he didn’t see any issue with the delay, especially if it meant preserving the investigation — even at the cost of keeping the public in the dark.

“Incident reports aren’t an instantaneous thing,” he said in an interview, stressing that the reports go up the chain of command for approvals and changes. “We release them when we can.”

Any incident report filed within the past 14 days is supposed to be made available the day requested, without a written request. These reports memorialize the nature and substance of reported crimes, not only as an investigative tool for police but also to inform citizens about the safety and well-being of their communities.

Once provided, though, these reports often lack the requisite substance. Key details of the alleged crime are either redacted or contained in separate documents, like supplemental reports. Advocates argue those, too, are public records to be available upon request. State lawmakers, in fact, changed the state open records law in 1998 to make clear that supplemental reports are public.

The heavily redacted report from Berkeley County made no mention of the shooting, except for the very first line of the document identifying the incident type as “information — shooting.”

Back in black

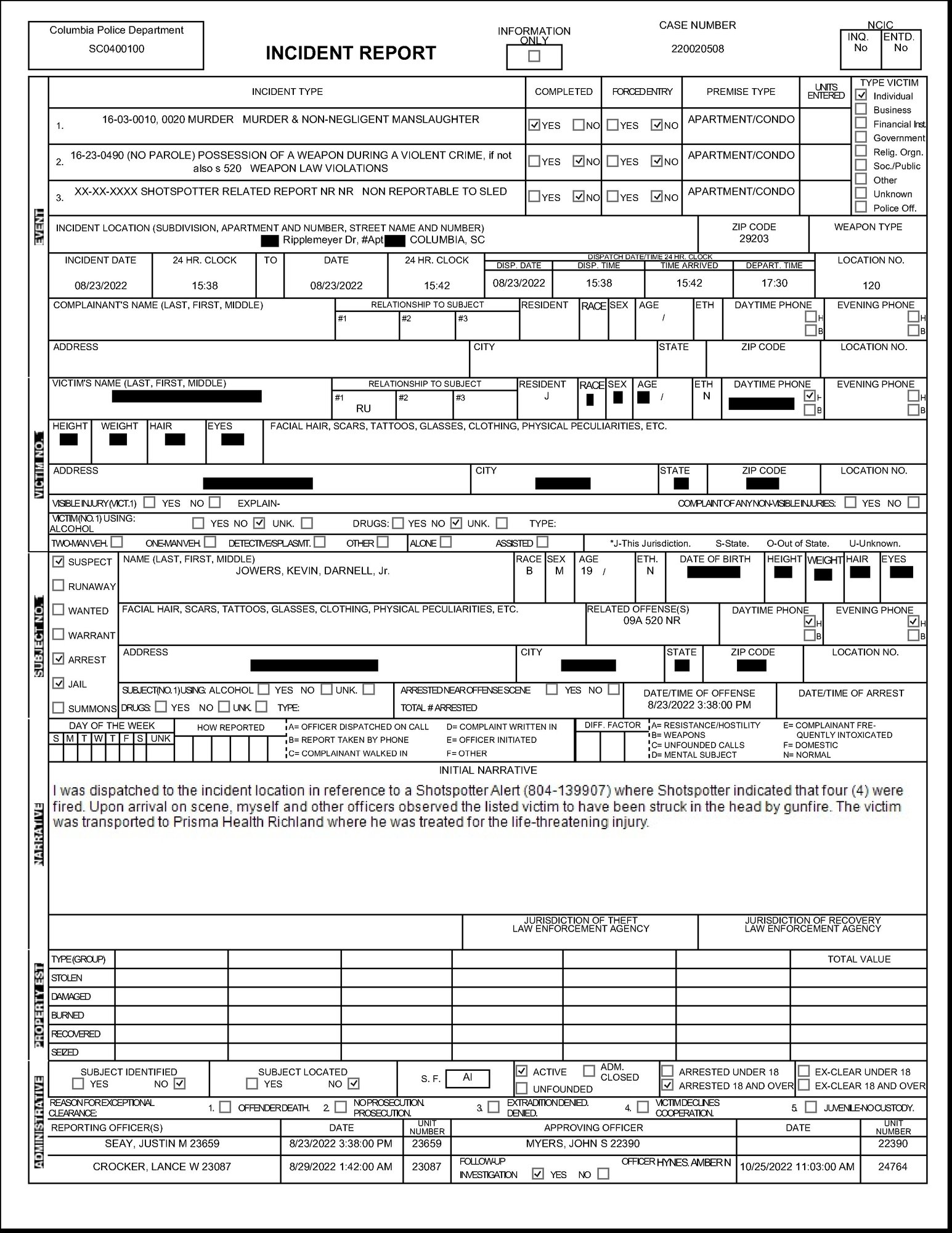

Columbia police are also well-known for their penchant for black ink, even in reference to cases they have used to push for reforms at the Statehouse or in city hall.

At a state Senate subcommittee hearing in January, Columbia Police Chief Skip Holbrook called for sweeping changes to the state’s bail bond system, citing a case he described as the worst example of system failure.

Holbrook detailed how one man had been accused of killing another in a Columbia housing project while out on bond in connection with a previous alleged murder in July. The chief delved into specifics of the case, saying that 14 people at or near the scene of the fatal shooting were wearing electronic ankle monitors.

The Post and Courier requested all documents related to the case to verify Holbrook’s public statements by assessing what officers wrote in their reports.

The department responded a week later with 26 pages of documents.

All but one page was entirely blacked out.

Only three sentences were visible on the first page. They described basic details of the initial response to the shooting. Nothing in those three sentences confirmed that 14 witnesses wore ankle monitors or much of the other information Holbrook shared with the subcommittee.

Timmons, the police spokeswoman, said the chief was operating within his discretion and the department in accordance with FOIA’s exemptions in withholding the information.

The law lists a number of exemptions, including the release of information that would

• “interfere with a prospective law enforcement proceeding”

• “constitute an unreasonable invasion of personal privacy,” and

•“endanger the life or physical safety of any individual.”

The loose wording, with no further explanations, has given police departments wide range in redacting and withholding information, open records advocates argue.

Jay Bender, a longtime press association attorney and FOIA expert, said he doesn’t believe the problem is the act itself; it’s a “failure to comply with the law” and a motivation by some officials “to capitalize on any potential language in the law to justify redaction.”

Bender said the most common reason he hears to justify redacting information is that a case “is under investigation.”

“Those words aren’t even in the law,” he said.

The Times and Democrat newspaper of Orangeburg recently ran into that problem while trying to report on a March 3 shooting at S.C. State University that left a student wounded at a campus housing facility.

The newspaper reported that campus police Chief Tim Taylor instructed a reporter a week later, on March 10, to file a FOIA request for an incident report even though a written request wasn’t required under the law. Taylor then sent the reporter to a university lawyer, who said S.C. State would not release the reports at all because they were part of “an active investigation in which no arrests have been made.”

No such exemption exists in the FOIA, but the reports have yet to surface all the same.

Overused exemptions

Open records advocates argue that another oft-abused provision in the law is the personal privacy exemption.

The FOIA says the exemption is meant to cover sensitive business financial information or personal information that could be used in solicitations to the disabled. But the law clearly states that this provision “must not be interpreted to restrict access by the public and press to information contained in public records.”

Yet police and other authorities have done just that time and again.

In the fall, Charleston County EMS officials refused to release reports on emergency responses to Detyens Shipyards in North Charleston, citing medical privacy exemptions related to accidents at the facility. Four workers had died within three years.

Goose Creek authorities recently cited the exemption in refusing to release crime scene photos and videos from a case that closed last February. Two people were found dead at a local home amid a federal tax fraud investigation.

These sorts of items were readily available in years past through an open records request. The law didn’t change; the interpretation did. And some advocates suspect it is being used to hide details the police would simply rather the public not know.

Charleston police used the privacy exemption to redact most of a search warrant in the recent investigation into the death of prominent attorney David Aylor. He was found dead in his Charleston home Jan. 2. An investigation would later pin the cause on an accidental drug overdose.

Before that conclusion was reached, police restricted most of the search warrant for his home from public view and carved out key details from its incident report — including the names of people at the house when officers arrived.

A Post and Courier reporter later obtained from a Charleston County magistrate court the same search warrant, revealing that police had blacked out the address of the home (which was already a matter of public record), as well as the fact that the house was white with black shutters. The example shows just how much discretion governments have to withhold information, and rarely does the public have the option to get the information elsewhere.

‘No real teeth’

Withholding such information makes it difficult for the public to see and understand how law enforcement is doing its job, press association attorneys Bender and Smith said.

And if they are caught violating the FOIA, there is little remedy for noncompliance, except to file suit in court.

“The law has no real teeth,” said Richard Whiting, executive editor of the Index-Journal in Greenwood who also serves as the S.C. Press Association’s new president and FOIA chair.

“I think they bank on, if you will, that most of the time is going to be too expensive,” Whiting said. “That newspapers aren’t going to do that. Certainly, individuals are not going to, unless they have very deep pockets.”

Public bodies often think of FOIA as an imposition, something extra, rather than a primary function of their jobs, Maye said.

“There are only like three reasons that public officials would not comply,” she said. “One is they’re ignorant of the law. The second is that they just don’t care about the law. And the third is that they’re afraid of public scrutiny.”

Local governments, like local news, are often understaffed, which could also contribute to noncompliance, Maye said.

“Either that’s going to reveal incompetence, at best, or, at worse, corruption,” Maye said. “And so, on its face, there’s just no good reason for public bodies not to comply.”

Caitlin Ashworth reported from Columbia and Ali Rockett from Charleston. Skylar Laird and Alexander Thompson contributed from Columbia, Spencer Donovan from Greenville and Glenn Smith from Charleston.

More Articles to Read