Uncovered: A Sumter, South Carolina, sheriff. A rape claim. And silence from SLED.

This article is part of The Post and Courier's Uncovered project, an ongoing initiative to shed light on corruption in South Carolina. The Post and Courier has partnered with 17 community newspapers across the state to bring investigative journalism to light. To read more Uncovered articles, go to https://www.postandcourier.com/uncovered/.

tbartelme@postandcourier.com

A former lieutenant with the Sumter County Sheriff’s Office told state authorities two years ago that longtime Sheriff Anthony Dennis raped her in his home in 1997 and groped her again in 2004 in a department office. She gave the State Law Enforcement Division names and other leads to corroborate her claims.

But SLED did little to verify or debunk her explosive allegations, a Post and Courier Uncovered investigation found. Agents didn't open a formal case, and there’s no evidence that detectives contacted people who might back up her statements.

In a letter to SLED Chief Mark Keel two weeks ago, the S.C. attorney general’s crime victims' ombudsman described the ex-lieutenant’s allegations as “very serious” and ones that “warrant a full investigation." Her letter followed months of document requests and questions about the case from The Post and Courier.

Keel told the newspaper on Jan. 19 that SLED will do a proper investigation. He explained that an agent who initially looked into the allegations died in late 2020.

"Unfortunately, and to be perfectly honest, it sort of fell through the cracks," Keel said.

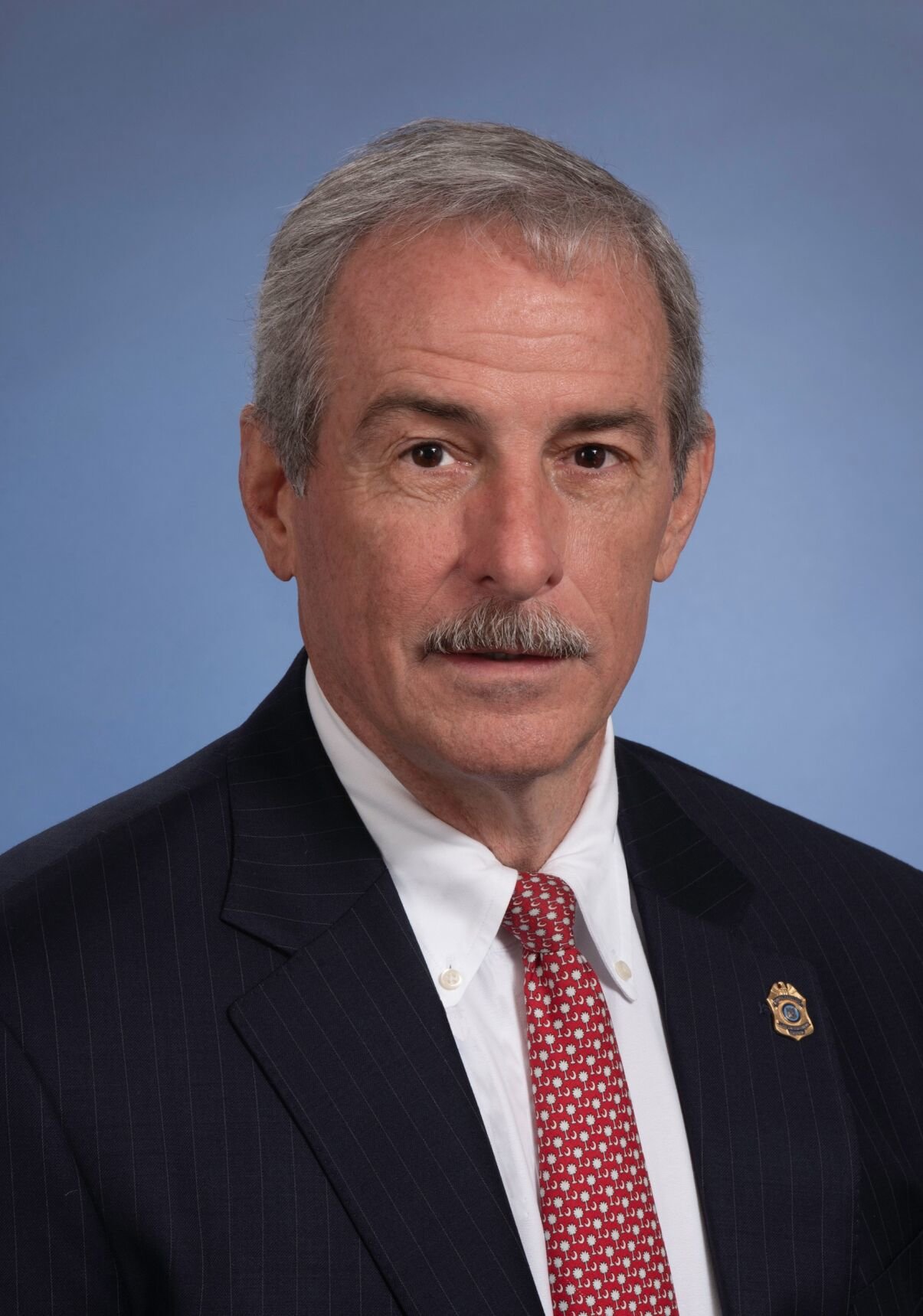

In an interview, Dennis said his accuser was a disgruntled former employee who had lost a previous lawsuit against his office.

"I blatantly deny all of those allegations," he said. "I have a 40-year career in law enforcement, and I can assure you that Sheriff Dennis has never sexually assaulted anyone or made any sexual advances, too."

He said he welcomes a SLED investigation.

Aside from the former lieutenant’s allegations, SLED’s slow walk toward a meaningful investigation in Sumter County raises fresh questions about how the agency handles sensitive claims against fellow law enforcement officials. The stakes are high: Haphazard and incomplete criminal investigations can mean the difference between justice delivered and justice denied.

The case in Sumter County also comes amid a growing train of sheriff scandals across South Carolina. Since 2010, 16 sheriffs have been accused of violating laws they swore to uphold. It’s a litany of corruption that affected one out of three South Carolina counties — so egregious that Gov. Henry McMaster earlier this month called for legislation requiring sheriffs undergo annual ethics training.

Was there also an abuse of power in Sumter County?

The allegation

Anthony Dennis began his law enforcement career in 1982, working his way up to major of operations in 1996 and chief deputy in 2000. He was elected Sumter County sheriff in 2004 and served as president of the S.C. Sheriffs’ Association in 2019. In 2020, the General Assembly passed a resolution honoring him for “exceptional leadership,” his work with youth groups in Sumter and for being one of Sumter County’s longest-serving sheriffs. He was reelected that year to a fifth term.

Melissa Addison joined the department in 1997 as an evidence technician under then-Sheriff Tommy Mims. She was in her early 30s, had separated from her husband and was struggling to make ends meet. Before, she'd held a series of grueling and mostly low-paying jobs: graveyard shift at a turkey processing plant, flipping fast-food burgers, factory work. Her new sheriff's office job was a godsend.

"I was a single parent with three kids, and now I had stable hours with an opportunity to advance," she recalled in an interview with The Post and Courier. "The job was beyond important to me."

She said that in the fall of 1997, she got a phone call from Dennis, who at the time was one of Mims' top commanders. Dennis asked her to come to his home and not to use her county vehicle, she alleged in a written statement she submitted to SLED in 2020.

“I was nervous about going but was too afraid not to go as he had given me a direct order.”

When she arrived, he asked her to go into his living room, she wrote in her statement. He began to make advances, she said.

“I was telling him ‘no’ and ‘to stop,’ but it fell on deaf ears.”

She alleged that he raped her, and that she left the house in tears.

She said she felt ashamed and fearful that no one would believe her.

“I believed that I would just end up looking like a fool and most likely lose my job that I very much needed,” her statement said.

She decided to not tell anyone and stay with the department.

"My children came first. I wasn't sure I'd get a job with that kind of income. I was just starting out in law enforcement. The uncertainty and risk was too much. So I stayed."

***

She said that over the next few years, she continued to balance her desire to succeed in law enforcement with depression and fear. She became a deputy and a criminal investigator.

Then, as Dennis was running for sheriff in 2004, he called her into his office and groped her, she alleged in her statement to SLED.

“I told him to stop … Dennis replied, ‘What are you going to do, get me for sexual harassment?’ ”

Addison said she decided to report what happened to Thomas Mims, the sheriff then, soon to retire. She drove to Mims’ house. Mims wasn’t home, but his wife, Diane, answered the door.

“I began crying,” Addison wrote in the SLED statement.

She said she left without mentioning what happened. Thomas Mims died in 2016.

Contacted recently by The Post and Courier, Diane Mims confirmed that Addison came to the house.

“I remember her. I remember her being in tears. She was very upset.”

Addison filed a complaint in February 2005 with the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, alleging that Dennis made sexual advances toward her. She didn’t report the sexual assault she says happened in 1997.

“This has been the worst experience of my life,” she wrote in that EEOC complaint, adding that she was afraid of reporting the incident to Sumter County’s human resource director because the sheriff’s wife held that job. (Lorraine Dennis is currently Sumter County assistant county administrator.)

But she quickly withdrew the complaint, in part because of “fear and terror” over what she believed Dennis could do to her “personally and professionally,” she told The Post and Courier.

Yet, during Dennis' tenure as sheriff, she continued to get plaudits for her work: She was named investigator of the year in 2006 and deputy of the year in 2007. Dennis promoted her to sergeant in 2009.

A story at that time in The Sumter Item quoted Dennis about his efforts to promote women: “I always brag about them. There’s not a female here that I wouldn’t send to do the same job that a male officer does,” he told the newspaper. In the same story, Addison said her promotion to sergeant “means the world. It’s validation of all the hard work I’ve done.”

But, in recent interviews with The Post and Courier, Addison said the weight of her secret only grew heavier over time. She finally told another deputy, Jerry Kelly.

Contacted by The Post and Courier, Kelly confirmed that conversation, which he said happened about 10 years ago.

“I was upset. I believed her. I’m not going to lie to you. We cried together through the whole conversation."

Kelly eventually left the department for a neighboring law enforcement job. Addison later identified Kelly as a potential witness, but he said that no one from SLED contacted him.

***

By 2015, she'd made lieutenant but then was sidelined into a lesser job.

In 2016, she filed a second discrimination complaint alleging that she was unfairly demoted because she is a Black woman. She did not report the alleged 1997 sexual assault.

“I wasn’t ready emotionally,” she said.

Then, during Christmas vacation 2016, a department major hand-delivered a letter to her.

"As you are aware, deputy sheriffs in South Carolina serve at the pleasure of the Sheriff," Dennis wrote in the letter. "I have decided not to renew your appointment." He included no other explanation for her termination.

The S.C. Human Affairs Commission declined to take the discrimination case, but Addison eventually sued the department. A jury found in favor of the sheriff in early 2019.

In December 2019, Addison wrote Keel at SLED that she’d sought counseling, and through this work, she realized that she needed to report her sexual abuse allegations.

“I am coming forward now as part of my recovery and because it is the right thing to do for me.”

The investigation

Last summer, The Post and Courier asked SLED for any documents related to Addison’s allegations. The state Freedom of Information Act allows the public access to files when investigators close a case. But a SLED spokesman said in October that the agency never opened a case, and that they couldn't locate any documents.

That was surprising given Addison supplied SLED with pages of statements and a witness list with phone numbers and addresses. Addison documented more than 80 emails, texts and other communications to and from SLED, many of which she shared with The Post and Courier. The newspaper contacted several people on her witness list. None said SLED contacted them.

Addison did meet with two SLED agents on Aug. 21, 2020, at SLED’s office in Florence. While agents often videotape or record interviews, SLED provided no recordings to The Post and Courier or written summaries of the interview.

This apparent failure to document a preliminary investigation appears to go against basic standards set by SLED’s accreditation agency, the Commission on Accreditation for Law Enforcement Agencies. Standards call for identification of witnesses, interviews and creation of case files.

Seth Stoughton, a criminal justice expert at the University of South Carolina and a former police officer, said most investigative activity should be documented. It's important to lock in details for future investigators, prosecutors and defense attorneys.

"That (documentation) may be in an investigative report, an intake screening report, a daily activity log or something," Stoughton said. "As a rule of thumb, the more formal the interaction, the more likely it is to be documented."

In contrast to SLED's questionable record-keeping, Addison kept close track of interviews, phone calls and emails. She even recorded conversations with SLED agents, including her initial meeting with them. She provided a copy to The Post and Courier.

It lasted for more than an hour and a half. Early on, SLED Capt. Johnnie Abraham, one of the agents, raised his voice and said he didn’t have much to work with.

“How can we substantiate what you’re saying? I’m not doubting something happened. Is there enough to do something with what you’re telling us?”

Addison submitted names of people to corroborate her elements of the story. She mentioned that one of her witnesses was a therapist she’d confided in. The second SLED agent interrupted her and incorrectly said the therapist should have immediately reported the allegation to police. (Therapists are not required to report rape allegations if their clients are adults.)

Addison broke down several times during that back-and-forth.

“I understand the tragedy of it,” the second agent said. “We need evidence to convince other people outside the room. … If you think of anyone I can talk to, call me.”

She continued to supply them with information.

In one phone recording, Abraham said, “I got everything you sent. I’ll recheck my file.”

In another, an unidentified agent told her: “I wish you had reported it to us when it happened, not several years after. Another problem is that you waited until after you lost your civil case before you reported it to us,” a reference to her 2016 discrimination claim and lawsuit. “That’s a problem.”

***

In an interview, Dennis said Abraham phoned him nearly two years ago "about some type of allegations … He mentioned sexual assault, that she had made allegations something to that effect." Dennis said he told Abraham that she had just lost her civil lawsuit at trial.

"I think (Abraham) knew what it was all about. I think Ms. Addison is upset she lost at trial, and it seems like she's continuing to give false statements."

Dennis said no one from SLED ever followed up.

Abraham, the SLED captain, died in December 2020.

As a former detective, Addison was aware that people might perceive her sexual assault allegations as sour grapes over losing her discrimination claim and lawsuit.

But some events she described to SLED happened before she filed that 2016 complaint. Details such as her emotional conversation with the wife of Sheriff Thomas Mims in 2004, her conversation with Jerry Kelly 10 years ago, her attempts to seek medical help for depression. She hoped that if agents confirmed those and other parts of her story, then they would be more confident she was telling the truth.

But SLED agents failed to document any follow-up interviews to corroborate these facts, The Post and Courier found.

Frustrated with SLED’s inaction, Addison wrote other public leaders, including the S.C. Attorney General’s crime victim ombudsman.

Justice delivered or delayed?

SLED has wide latitude when it comes to opening cases, its policies show. The agency can open cases based on requests from a private citizen, another agency or the governor and do so based on the nature of the allegation and “availability of SLED resources.”

On Dec. 29, 2021, Veronica Swain Kunz, the S.C. Attorney General’s crime victim ombudsman, wrote to SLED about Addison’s case.

In her letter, she wrote that she’d asked SLED for records of its work, but that SLED was unable to find any. She urged SLED to open a full investigation.

“At this point, I would like to see a case opened and an agent (who has no association with Sumter County) assigned to work with Ms. Addison to get to the bottom of the issue,” she wrote.

Keel acknowledged that mistakes were made early on. The agency should have opened a formal case, which would have triggered a review process.

"But the bottom line is that it kind of went off the radar after he (Abraham) passed away."

Keel said the agency did eventually find a file of materials, but only recently — after Kunz from the Attorney General's Office sent the letter.

"I've talked to the sheriff, and he asked me to open an investigation," Keel said. "And, of course, we had already planned on doing it anyway."

As far as violating any of the agency's standards, he said, "We're not perfect. We all make mistakes sometimes. We're going to go back and do the best we can to correct any mistakes."

To be sure, SLED often has its hands full, with agents tasked to investigate everything from police shootings to the sprawling investigations into the Murdaugh family shootings last summer and spin-off probes into the powerful Hampton County family's real estate and banking empire.

But when it comes to investigating fellow law enforcement officers, its performance has been mixed.

In recent years, the agency successfully collared high-profile sheriffs, often working with the FBI. This includes cases against former Chester County Sheriff Alex Underwood and former Colleton County Sheriff Andy Strickland, both of whom were convicted of using their public positions for personal gain.

But the agency bungled other cases. In the mid-2000s, for instance, agents failed to properly investigate the death of a Mount Pleasant pharmacist, whose boyfriend was a police officer. It was botched so badly the Charleston County Coroner held a rare inquest and SLED was forced to do another investigation. The agent assigned to the original case was fired and two commanders were reprimanded.

The Post and Courier’s 2015 “Shots Fired” analysis of police shootings also uncovered case after case where SLED agents failed to answer key questions about what happened, failed to document the troubled backgrounds of the officers who drew their guns, and failed to pinpoint missteps and tactical mistakes that could be used to prevent future bloodshed.

In Sumter County’s case, SLED’s failure to investigate a serious allegation has left both accuser and accused in limbo.

Dennis said he feels like he's the target of "a personal vendetta" that could be damaging "to my career and my office. And my family is going to be affected."

Addison said sexual abuse victims often take years to come to terms with what happened and come forward, and she said she's an example of that.

"I can't die with this inside me."

As for SLED's initial response to allegations, she said she felt as if they never took it seriously, a form of injustice in itself.

Editor’s note: This story was done in collaboration with The Sumter Item, an Uncovered partner.

More Articles to Read